Topic: Paleo Diet

We are not biologically identical to our Paleolithic predecessors, nor do we have access to the foods they ate. And deducing dietary guidelines from modern foraging societies is difficult because they vary so much by geography, season and opportunity

Meet Grok. According to his online profile, he is a tall, lean, ripped and agile 30-year-old. By every measure, Grok is in superb health: low blood pressure; no inflammation; ideal levels of insulin, glucose, cholesterol and triglycerides. He and his family eat really healthy, too. They gather wild seeds, grasses, and nuts; seasonal vegetables; roots and berries. They hunt and fish their own meat. Between foraging, building sturdy shelters from natural materials, collecting firewood and fending off dangerous predators far larger than himself, Grok’s life is strenuous, perilous and physically demanding. Yet, somehow, he is a stress-free dude who always manages to get enough sleep and finds the time to enjoy moments of tranquility beside gurgling creeks. He is perfectly suited to his environment in every way. He is totally Zen.

Ostensibly, Grok is “a rather typical hunter–gatherer” living before the dawn of agriculture—an “official primal prototype.” He is the poster-persona for fitness author and blogger Mark Sisson’s “Primal Blueprint”—a set of guidelines that “allows you to control how your genes express themselves in order to build the strongest, leanest, healthiest body possible, taking clues from evolutionary biology (that’s the primal part).” These guidelines incorporate many principles of what is more commonly known as the Paleolithic, or caveman, diet, which started to whet people’s appetites as early as the 1960s and is available in many different flavors today.

Proponents of the Paleo diet follow a nutritional plan based on the eating habits of our ancestors in the Paleolithic period, between 2.5 million and 10,000 years ago. Before agriculture and industry, humans presumably lived as hunter–gatherers: picking berry after berry off of bushes; digging up tumescent tubers; chasing mammals to the point of exhaustion; scavenging meat, fat and organs from animals that larger predators had killed; and eventually learning to fish with lines and hooks and hunt with spears, nets, bows and arrows.

Most Paleo dieters of today do none of this, with the exception of occasional hunting trips or a little urban foraging. Instead, their diet is largely defined by what they do not do: most do not eat dairy or processed grains of any kind, because humans did not invent such foods until after the Paleolithic; peanuts, lentils, beans, peas and other legumes are off the menu, but nuts are okay; meat is consumed in large quantities, often cooked in animal fat of some kind; Paleo dieters sometimes eat fruit and often devour vegetables; and processed sugars are prohibited, but a little honey now and then is fine.

Almost equal numbers of advocates and critics seem to have gathered at the Paleo diet dinner table and both tribes have a few particularly vociferous members. Critiques of the Paleo diet range from the mild—Eh, it’s certainly not the worst way to eat—to the acerbic: It is nonsensical and sometimes dangerously restrictive. Most recently, in her book Paleofantasy, evolutionary biologist Marlene Zuk of the University of California, Riverside, debunks what she identifies as myths central to the Paleo diet and the larger Paleo lifestyle movement.

Most nutritionists consent that the Paleo diet gets at least one thing right—cutting down on processed foods that have been highly modified from their raw state through various methods of preservation. Examples include white bread and other refined flour products, artificial cheese, certain cold cuts and packaged meats, potato chips, and sugary cereals. Such processed foods often offer less protein, fiber and iron than their unprocessed equivalents, and some are packed with sodium and preservatives that may increase the risk of heart disease and certain cancers.

But the Paleo diet bans more than just highly processed junk foods—in its most traditional form, it prohibits any kind of food unavailable to stone age hunter–gatherers, including dairy rich in calcium, grains replete with fiber, and vitamins and legumes packed with protein. The rationale for such constraint—in fact the entire premise of the Paleo diet—is, at best, only half correct. Because the human body adapted to life in the stone age, Paleo dieters argue—and because our genetics and anatomy have changed very little since then, they say—we should emulate the diets of our Paleo predecessors as closely as possible in order to be healthy. Obesity, heart disease, diabetes, cancer and many other “modern” diseases, the reasoning goes, result primarily from the incompatibility of our stone age anatomy with our contemporary way of eating.

Diet has been an important part of our evolution—as it is for every species—and we have inherited many adaptations from our Paleo predecessors. Understanding how we evolved could, in principle, help us make smarter dietary choices today. But the logic behind the Paleo diet fails in several ways: by making apotheosis of one particular slice of our evolutionary history; by insisting that we are biologically identical to stone age humans; and by denying the benefits of some of our more modern methods of eating.

“‘Paleofantasies’ call to mind a time when everything about us—body, mind, and behavior—was in sync with the environment…but no such time existed,” Zuk wrote in her book. “We and every other living thing have always lurched along in evolutionary time, with the inevitable trade-offs that are a hallmark of life.”

On his website, Sisson writes that “while the world has changed in innumerable ways in the last 10,000 years (for better and worse), the human genome has changed very little and thus only thrives under similar conditions.” This is simply not true. In fact, this reasoning misconstrues how evolution works. If humans and other organisms could only thrive in circumstances similar to the ones their predecessors lived in, life would not have lasted very long.

Several examples of recent and relatively speedy human evolution underscore that our anatomy and genetics have not been set in stone since the stone age. Within a span of 7,000 years, for instance, people adapted to eating dairy by developing lactose tolerance. Usually, the gene encoding an enzyme named lactase—which breaks down lactose sugars in milk—shuts down after infancy; when dairy became prevalent, many people evolved a mutation that kept the gene turned on throughout life. Likewise, the genetic mutation responsible for blue eyes likely arose between 6,000 and 10,000 years ago. And in regions where malaria is common, natural selection has modified people’s immune systems and red blood cells in ways that help them resist the mosquito-borne disease; some of these genetic mutations appeared within the last 10,000 or even 5,000 years. The organisms with which we share our bodies have evolved even faster, particularly the billions of bacteria living in our intestines. Our gut bacteria interact with our food in many ways, helping us break down tough plant fibers, but also competing for calories. We do not have direct evidence of which bacterial species thrived in Paleolithic intestines, but we can be sure that their microbial communities do not exactly match our own.

Even if eating only foods available to hunter–gatherers in the Paleolithic made sense, it would be impossible. As Christina Warinner of the University of Zurich emphasizes in her 2012 TED talk, just about every single species commonly consumed today—whether a fruit, vegetable or animal—is drastically different from its Paleolithic predecessor. In most cases, we have transformed the species we eat through artificial selection: we have bred cows, chickens and goats to provide as much meat, milk and eggs as possible and have sown seeds only from plants with the most desirable traits—with the biggest fruits, plumpest kernels, sweetest flesh and fewest natural toxins. Cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts and kale are all different cultivars of a single species, Brassica oleracea; generation by generation, we reshaped this one plant’s leaves, stems and flowers into wildly different arrangements, the same way we bred Welsh corgis, pugs, dachshunds, Saint Bernards and greyhounds out of a single wolf species. Corn was once a straggly grass known as teosinte and tomatoes were once much smaller berries. And the wild ancestors of bananas were rife with seeds.

The Paleo diet not only misunderstands how our own species, the organisms inside our bodies and the animals and plants we eat have evolved over the last 10,000 years, it also ignores much of the evidence about our ancestors’ health during their—often brief—individual life spans (even if a minority of our Paleo ancestors made it into their 40s or beyond, many children likely died before age 15). In contrast to Grok, neither Paleo hunter–gatherers nor our more recent predecessors were sculpted Adonises immune to all disease. A recent study in The Lancet looked for signs of atherosclerosis—arteries clogged with cholesterol and fats—in more than one hundred ancient mummies from societies of farmers, foragers and hunter–gatherers around the world, including Egypt, Peru, the southwestern U.S and the Aleutian Islands. “A common assumption is that atherosclerosis is predominately lifestyle-related, and that if modern human beings could emulate preindustrial or even preagricultural lifestyles, that atherosclerosis, or least its clinical manifestations, would be avoided,” the researchers wrote. But they found evidence of probable or definite atherosclerosis in 47 of 137 mummies from each of the different geographical regions. And even if heart disease, cancer, obesity and diabetes were not as common among our predecessors, they still faced numerous threats to their health that modern sanitation and medicine have rendered negligible for people in industrialized nations, such as infestations of parasites and certain lethal bacterial and viral infections.

Some Paleo dieters emphasize that they never believed in one true caveman lifestyle or diet and that—in the fashion of Sisson’s Blueprint—they use our evolutionary past to form guidelines, not scripture. That strategy seems reasonably solid at first, but quickly disintegrates. Even though researchers know enough to make some generalizations about human diets in the Paleolithic with reasonable certainty, the details remain murky. Exactly what proportions of meat and vegetables did different hominid species eat in the Paleolithic? It’s not clear. Just how far back were our ancestors eating grains and dairy? Perhaps far earlier than we initially thought. What we can say for certain is that in the Paleolithic, the human diet varied immensely by geography, season and opportunity. “We now know that humans have evolved not to subsist on a single, Paleolithic diet but to be flexible eaters, an insight that has important implications for the current debate over what people today should eat in order to be healthy,” anthropologist William Leonard of Northwestern University wrote in Scientific American in 2002.

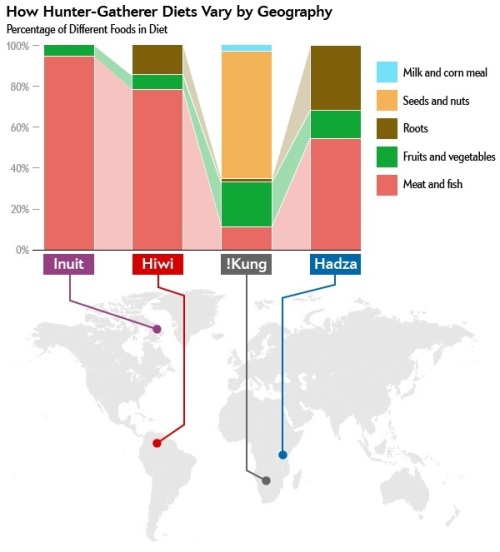

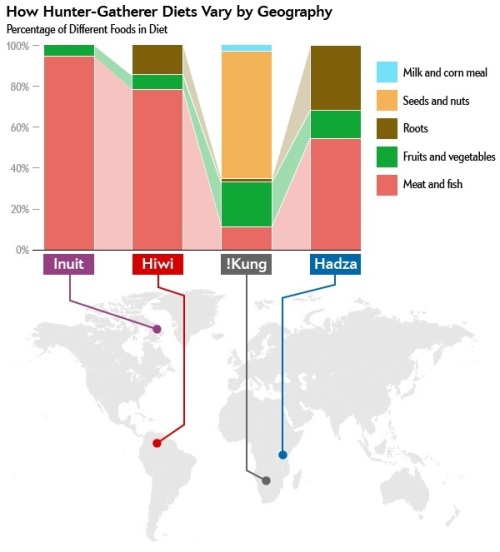

We cannot time travel and join our Paleo ancestors by the campfire as they prepare to eat; likewise, shards of ancient pottery and fossilized teeth can tell us only so much. If we compare the diets of so-called modern hunter-gatherers, however, we see just how difficult it is to find meaningful commonalities and extract useful dietary guidelines from their disparate lives (see infographic). Which hunter–gatherer tribe are we supposed to mimic, exactly? How do we reconcile the Inuit diet—mostly the flesh of sea mammals—with the more varied plant and land animal diet of the Hadza or !Kung? Chucking the many different hunter–gather diets into a blender to come up with some kind of quintessential smoothie is a little ridiculous. “Too often modern health problems are portrayed as the result of eating ‘bad’ foods that are departures from the natural human diet…This is a fundamentally flawed approach to assessing human nutritional needs,” Leonard wrote. “Our species was not designed to subsist on a single, optimal diet. What is remarkable about human beings is the extraordinary variety of what we eat. We have been able to thrive in almost every ecosystem on the Earth, consuming diets ranging from almost all animal foods among populations of the Arctic to primarily tubers and cereal grains among populations in the high Andes.”

Closely examining one group of modern hunter–gatherers—the Hiwi—reveals how much variation exists within the diet of a single small foraging society and deflates the notion that hunter–gatherers have impeccable health. Such examination also makes obvious the immense gap between a genuine community of foragers and Paleo dieters living in modern cities, selectively shopping at farmers’ markets and making sure the dressing on their house salad is gluten, sugar and dairy free.

By latest count, about 800 Hiwi live in palm thatched huts in Colombia and Venezuela. In 1990 Ana Magdalena Hurtado and Kim Hill—now both at Arizona State University in Tempe—published a thorough study (pdf) of the Hiwi diet in the neotropical savannas of the Orinoco River basin in Southwestern Venezuela. Vast grasslands with belts of forest, these savannas receive plenty of rain between May and November. From January through March, however, precipitation is rare: the grasses shrivel, while lakes and lagoons evaporate. Fish trapped in shrinking pools of water are easy targets for caiman, capybaras and turtles. In turn, the desiccating lakes become prime hunting territory for the Hiwi. During the wet season, however, the Hiwi mainly hunt for animals in the forest, using bows and arrows.

The Hiwi gather and hunt a diverse group of plants and animals from the savannas, forests, rivers and swamps. Their main sources of meat are capybara, collared peccary, deer, anteater, armadillo, and feral cattle, numerous species of fish, and at least some turtle species. Less commonly consumed animals include iguanas and savanna lizards, wild rabbits, and many birds. Not exactly the kind of meat Paleo dieters and others in urban areas can easily obtain.

Five roots, both bitter and sweet, are staples in the Hiwi diet, as are palm nuts and palm hearts, several different fruits, a wild legume named Campsiandra comosa, and honey produced by several bee species and sometimes by wasps. A few Hiwi families tend small, scattered and largely unproductive fields of plantains, corn and squash. At neighboring cattle ranches in a town about 30 kilometers away, some Hiwi buy rice, noodles, corn flour and sugar. Anthropologists and tourists have also given the Hiwi similar processed foods as gifts (see illustration at top).

Hill and Hurtado calculated that foods hunted and collected in the wild account for 95 percent of the Hiwi’s total caloric intake; the remaining 5 percent comes from store-bought goods as well as from fruits and squash gathered from the Hiwi’s small fields. They rely more on purchased goods during the peak of the dry season.

The Hiwi are not particularly healthy. Compared to the Ache, a hunter–gatherer tribe in Paraguay, the Hiwi are shorter, thinner, more lethargic and less well nourished. Hiwi men and women of all ages constantly complain of hunger. Many Hiwi are heavily infected with parasitic hookworms, which burrow into the small intestine and feed on blood. And only 50 percent of Hiwi children survive beyond the age of 15.

Drop Grok into the Hiwi’s midst—or indeed among any modern or ancient hunter–gather society—and he would be a complete aberration. Grok cannot teach us how to live or eat; he never existed. Living off the land or restricting oneself to foods available before agriculture and industry does not guarantee good health. The human body is not simply a collection of adaptations to life in the Paleolithic—its legacy is far greater. Each of us is a dynamic assemblage of inherited traits that have been tweaked, transformed, lost and regained since the beginning of life itself. Such changes have not ceased in the past 10,000 years.

Ultimately—regardless of one’s intentions—the Paleo diet is founded more on privilege than on logic. Hunter–gatherers in the Paleolithic hunted and gathered because they had to. Paleo dieters attempt to eat like hunter–gatherers because they want to.

Original article:

scientific american

by Ferris Jabr, June 28, 2013

By Jen Christiansen

The Hiwi Diet

What a group of hunter-gatherers in Colombia and Venezuela eat

Palm nuts and heart (Mauritia flexuosa)Brazilian Teal (Amazonetta brasiliensis)Wild root “Yatsiro” (Canna edulis)Red Brocket deer (Mazama americana)Wild root “No’o” (Dioscorea)Wild root “Oyo” (Banisteriopsis)Armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus)Guava (Psidium guava)Yellow-spotted river turtle (Podocnemis unifilis)Wild root “Hewyna” (Calathea allouia)Mata Mata turtle (Chelus fimbriatus)Capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris)Silver Mylosomma (Mylossoma duriventre)Iguana (Iguana iguana)Iguana (Iguana iguana)Orange (Citrus x sinensis)Roseate Spoonbill (Ajaja ajaja)Roseate Spoonbill (Ajaja ajaja)Collared peccary (Pecari tajacu)Wild rabbit (Sylvilagus varynaensis)Piranha (Serrasalmus)Trahira (Hoplias malabaricus)Collared anteater (Tamandua tetradactyla)Gold Tegu (Tupinambis teguixin)Mangoes (Mangifera)Wild legume “Chiga” (Campsiandra comosa)South American catfish (Pseudoplatystoma)Charichuelo (Garcinia madruno)Yellow-footed tortoise (Chelonoidis denticulata)Caiman (Caiman crocodilus)

by Marissa Fessenden

Read Full Post »

Explore further: Ancient fish hooks found on Okinawa suggest earlier maritime migration than thought